The human body is home to trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, yeasts, and viruses, which inhabit areas such as your skin, nose, mouth, and gut. A significant portion of these microbes are found in the gut, where they play a vital role in maintaining your health by influencing hormone balance, metabolism, immune function, and digestion. However, their impact goes beyond these functions – gut bacteria have been linked to various health conditions, including metabolic disorders like obesity and type 2 diabetes, as well as mental health issues. This article delves into the role of gut bacteria and their effects on overall well-being.

Better4U partner, The European Food Information Council has written an article on “What is the role of gut bacteria in human health?” exploring what gut bacteria are and how they affect our overall health.

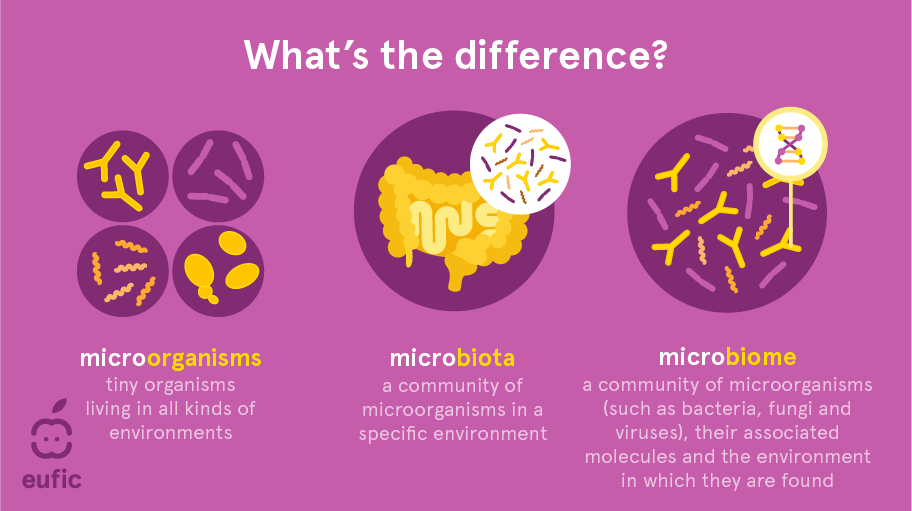

Fig 1 – Illustration of the difference between microorganisms, microbiota, microbiome

The EU-funded BETTER4U project is working to develop personalised interventions to address obesity and weight gain. The project aims to understand how factors like genetics, epigenetics, lifestyle, environment, and the gut microbiome influence weight gain and to identify potential microbial strains that could aid in weight loss.

Fig. 2 – What factors influence the gut microbiota?

This article was written in collaboration with EUFIC and researchers from the DOMINO and BETTER4U projects.

📢 View the article on EUFIC’s website, here.